5 Irresistible Customer Incentives

Consumer minds of today are jaded. Discounts wait on every corner, the allure of a simple good deal has worn off. Still, no need to plunge into the price war – our brains are hardwired to react to a whole lot of other incentives.

Simply put, an incentive is something that encourages a person to do something. From a business perspective, that person is a (future) customer and what we want them to do is make a purchase, or at least leave us their contact details for later follow-up.

But as with all enticements, the appeal of customer incentives can subside and shift over time. For example consumers have grown to expect more than a fair price for a good product. As Lemonstand reports, 50 percent of them only buy on offer or promotion. Consequently, business success increasingly hinges on providing extra value.

The default action for most vendors is to slash prices, inviting all the pitfalls that go along with a discount strategy, as HubSpot’s Alyssa Rimmer pointed out in her post .

Let's look at the consumer’s softest spots, and how to play into them with clever incentives.

1

Scarcity

Humans elevate the value of items whose availability appears limited. Their present-day preference for things in short supply likely is evolutionary baggage. Scarcity and competition probably already led to violence between our prehistoric ancestors.

But even in times of abundance, we just can’t get over our fear of missing out. Worchel, Lee and Adewole proved this in 1975 with cookies, items far from being life-essentials. Still, when the jar was nearly empty, the subjects assigned the treats a significantly higher value. Competition further increased the effect.

On websites the scarcity incentive is popularly reproduced by showing visitors the remaining number of items in stock. But in order to create a stronger sense of urgency, so suggests the temporal motivation theory , the stock’s finiteness needs to be connected to a time limit. The end is much more scary and thus motivating when it’s near.

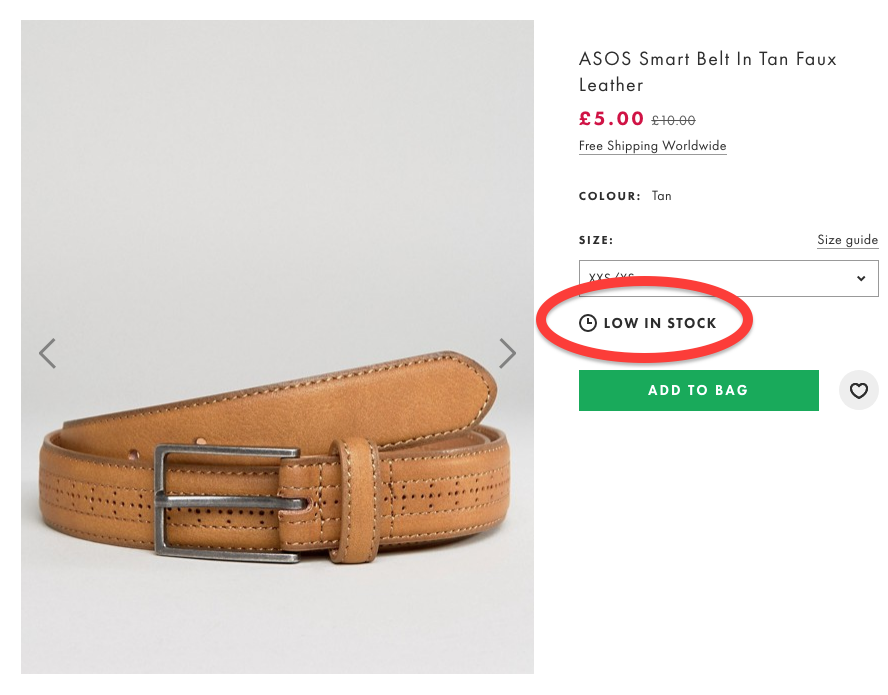

That’s why many sites don’t let their customers guess whether the displayed number of remaining items suggests “buy now!” or “let’s give it some thought” – they simply say it’s nearly sold out. Check out ASOS’ example below.

Although these labels apparently still get the job done, savvy shoppers often mistrust their truthfulness. Such words don’t just set off alarm bells in customer minds. Econsultancy posted a list of spam triggers in email marketing , and, sure enough, “sale”, “soon”, and “% off” made it.

Booking.com takes this tactic to a different level. The platform indicates the number of people also looking at the accommodation, how often it was booked within the last hours, and that the chosen dates are generally highly competitive. They even say “you missed it!” once a place is booked out, adding a pinch of reproach so that visitors decide quicker next time.

While ASOS’ information is useful for the visitor, booking.com’s has the sole purpose to create pressure. It’s good to know how many pieces of the product you’re looking at lie in the shelf before your eyes. A couple of people following you through the store to act as competitors is just wrong.

2

Loss aversion

Kahneman’s and Tversky’s 1979 concept of loss aversion says that we suffer more from perceived losses than equivalent gains make us happy. This translates to overvaluing things we seem to possess and a strong intend to keep them. And an incentive that focuses on the offer to prevent a loss.

But possession isn’t limited to material objects, and the feeling of ‘owning’ something builds up rather quickly. Gazing at a discounted product is enough to make us feel like owning the current price – and fearing that we might lose it if we buy later when the price rises again.

Most often, the element the customer is supposed to fear losing has nothing to do with the product it’s attached to. This enables businesses to add the same customer incentive to a great range of products. A popular example is when value is added based on the amount of money spent, like discounts or free shipping.

Ticket shops use the same systematic in their tiered pricing models for events. If you don’t buy the early bird ticket, you know that you’ll soon lose the special offer. By displaying sold out ticket categories, the Primavera Sound festival also adds a scarcity incentive. See below.

The loss aversion incentive also works when the product itself is framed as the cure for anticipated losses. We all know the detergent bottle promoting to preserve the colors of your clothes.

Use aspirational messaging. Be real in your messaging. Aim to be a problem-solver, and help your users take constructive action.

Ritika Puri, Storyhackers

If you look at ads by banks today, you’ll recognize the same incentive. They increasingly depict themselves as cautious problem solvers instead of wealthy fortune hunters. Especially in light of dropping interest and rising inflation rates, the fear of loss is a much stronger incentive.

Ritika Puri advocates a new form of incentivizing loss aversion in her Relate Mag article : helpful messages instead of pushy sales, leading to actions that benefit both sides of the counter.

3

Instant gratification

Most of the stuff we order online can be used but won’t be needed soon enough to justify the great success of high-speed delivery. Sure, the express parcel might save a couple of marriages close to the holidays. But the actual reason for the success of Prime & co is that when we can get immediate satisfaction, we take it. We even trade in long-term benefits for that.

One of the lessons digital natives are being taught by our culture is that it’s no longer necessary to wait for experiences or goals.

Russell C. Smith, Michael Foster, Psychology Today

You can look for evolutionary advantages of instant gratification and will find plausible answers in the daily routines of our hunter-gatherer-ancestors. All that mattered for them had to be the present day. But in the digital age, we’re downright nurturing that biological preset with instant notifications and ever-quicker processes. Not least, because it’s a great incentive for driving action.

First and foremost, instant gratification incentives motivate buying decisions and purchases. Provide and highlight quick delivery options and offer them for free in certain conditions for upselling.

Once the visitor has made the decision to buy, the effect has to be preserved. KISSmetrics aptly describes how easily the customer experience breaks down between cart and checkout, stealing all that instant gratification thunder. Quick user onboarding and simple checkout processes keep the pace up. Additional customer data may be valuable, but first of all, you want to motivate a signup or purchase.

To limit the annoyance of registrations and to speed up processes, quick logins via social network accounts are standard by now. Also, online retailers increasingly offer visitors to order as guest and avoid cumbersome registration altogether.

The quickest delivery involves some waiting, which our impatient minds naturally dislike. As The Psychology of Waiting Lines tells us, waiting time is sweetened by information about how long it will be and what the reason is. Use this by offering customers frequent delivery status updates right to their mobile phone. It will assure an uninterrupted experience of how fast it all goes.

4

Social conscience appeal

We buy a TV set knowing about the multitude of rare materials used to build it, with all the human labor involved in extraction. That home cinema feel obviously helps blank out such things.

Still, consumers gratifyingly care more and more about ethical questions . In fact, most of our material purchases lack greater purpose. Or at least – here’s another incentive – there’s plenty of room to add some.

The added value for customers does not lie in the option to do good. It lies in making it easy. Customers could as well look for a cheaper alternative and donate the saved money to an organization of their own choice. But that would require extra effort (remember instant gratification).

Looking for better customer relationships?

Test Userlike for free and chat with your customers on your website, Facebook Messenger, and Telegram.

Read moreSo, how to use the lifted social conscience as an incentive? If you’re selling green electricity, practical use and good deed blend in wonderfully. But if the product itself can’t promise to do any good, the money spent on it absolutely can.

You could let a fixed percentage of any purchase go to organization X. German beer giants Krombacher launched a famous campaign about 20 years ago, connecting every beer case sold to support funds for preserving the Congolese rainforest . After initially being accused of greenwashing, the company eventually dramatically improved its sales and its image.

Obviously, greenwashing is (a) bad (idea). If you use social conscience incentives, they should come with further information about the organizations and causes you support and be rooted in your company’s core values .

5

Social proof

Like it or not, but we’re not so individual after all. Social animals that we are, being the stubborn loner was surely not an evolutionary advantage throughout humanity’s history. Still today, the most modern individual trusts in what allegedly knowledgeable others say. We base our decisions on the opinion of peers, experts, or simply huge numbers of people.

Consequently, showing how many, which, and why others bought a product will influence our decision to buy it. Here’s a quick overview of the types of social proof and the incentives they suggest:

- Bandwagon effect. People believe things because a certain number of others does. A great number of purchases works as an incentive to buy the same product. If the number is big enough, it doesn’t matter who made the purchase or how well the product works for them.

- In-group favoritism. People favor things because members of their own ‘group’ do. Those are people with shared beliefs, attitudes, taste or values. With this incentive you can even get the ones that call themselves all independent – just link them up with other mainstream-sceptics and they’ll follow each other blindly. For instance, use social media plugins like that of Facebook to show a customer who of her buddies likes your company.

- Authority bias. The consent of experts is a strong incentive. That’s why you’ll find “Top Reviewers” suggesting higher credibility in every Amazon review column. Other incentives are testimonials and ratings and the display of renowned product users.